50 Years of the New Mass: Pius XII’s Encyclical Mystici Corporis (17)

Pope Pius XII, Eugenio Pacelli, whose pontificate extended from 1939 to 1958, vigorously fought against the modern errors that continued to spread in the Church in his day, despite St. Pius X’s condemnations.

Pope Pacelli’s main intervention against modernism was the encyclical Humani generis, dated August 12, 1950. It addresses three main issues that agitated post-war Catholicism: the authority of the Magisterium of the Church to prescribe what one must believe in divine revelation; the value and role of reason; and the problems that history and the modern natural or physical sciences pose to the Church.

The encyclical faces two problems that are still very much present today: 1) the questions that advances and discoveries of history and the natural sciences pose to traditional doctrine and the revisions they may impose on the Church; and, 2) doctrinal relativism to restore Christian unity and to respond to the aspirations of a large number of Christians, as demonstrated by the Protestants with the establishment of the Church Ecumenical Council in 1948.

Thus, the encyclical Humani generis can be compared to the encyclical Pascendi of St. Pius X. Indeed, Pius XII reiterated the condemnations of his predecessor, whom he canonized four years later.

But prior to this condemnation of “false opinions that threaten to ruin the foundations of Catholic doctrine,” Pope Pius XII had already stigmatized the new doctrinal tendencies that undermined Catholicism through three encyclicals: Mediator Dei dealing with the liturgy (November 20, 1947), Mystici corporis dealing with the Church (June 29, 1943), and Divino afflante spiritu addressing the field of biblical exegesis, one of the most important hotbeds of modernism (September 30, 1943).

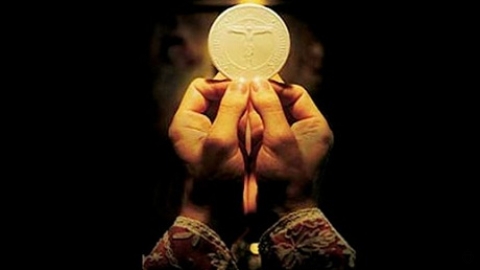

The Encyclical Mystici Corporis

Chronologically, Mystici corporis is the first of the great encyclicals of Pius XII. It is dated June 29, 1943, in the midst of the Second World War.

During the interwar period, the theology of the Mystical Body was greatly developed, under the influence of the First Vatican Council, which had identified this revealed concept with the Church, but some theologians also used the concept to fuel their points of contention against the institutional Church, as represented by the pope and the bishops. This opposition, which can be described as dialectic, was well in line with what was denounced by Saint Pius X in Pascendi as early as 1907.

The latter described the tension between popular belief and doctrinal and dogmatic authority. This tension justified the necessary progress that had to be made by authorities taking into consideration the experiences of believers. This idea snakes among theologians who want to see the Church evolve in all areas, especially as regards its understanding of itself as Church.

Condemend Theories

The encyclical condemns “grave errors” and “inaccurate or thoroughly false ideas.” The first consists of a “false rationalism, which ridicules anything that transcends and defies the power of human genius,” associated with “a cognate error, the so-called popular naturalism.” The second is “a false mysticism creeping in, which, in its attempt to eliminate the immovable frontier that separates creatures from their Creator, falsifies the Sacred Scriptures.”

The second error tends to reduce the Church to a spiritual and invisible society, in the manner of Protestantism. The first sees “in the Church nothing but a juridical and social union.” This is how it distinguishes between the “Catholic Church” and the “Church of Christ,” refusing to associate them. The foundation of modern ecumenism can be found in its embryonic form in this refusal. Pope Pius XII shows in the encyclical that the two terms must be associated.

The Liturgy in Mystici Corporis

On the occasion of this beautiful presentation of the Church, the encyclical tackles various points relating to the liturgy. This is easily understood since an error about the Church produces consequences in many areas: dogmatic, spiritual, liturgical, canonical.

Contempt for Frequent Confession

The basis of the error is dogmatic. Some of the innovators, misunderstanding the union of Christ and the faithful in the Mystical Body, attribute “the whole spiritual life of Christians and their progress in virtue exclusively to the action of the Divine Spirit, setting aside and neglecting the collaboration which is due from us.”

Certainly, the Spirit of Jesus Christ is the sole source of all life which circulates in the Mystical Body. However, it takes the cooperation of the human will to the sanctification that this Spirit pours into souls. By denying it, we fall into the grave error of quietism, which, according to its etymology, consists in rest—quies in Latin—a complete rest where we exert no effort to assist with our sanctification. Pope Pius XII strongly condemns such an error.

The latter brings about a liturgical error: “The same result follows from the opinions of those who assert that little importance should be given to the frequent confession of venial sins. Far more important, they say, is that general confession which the Spouse of Christ, surrounded by her children in the Lord, makes each day by the mouth of the priest as he approaches the altar of God.”

In other words, since the priests—and the faithful who attend their Masses—confess sins every day on behalf of the members of the Church, it is not necessary to go to confession frequently, especially if there is only venial sins to confess. Pius XII wants to refute this error of liturgical origin, an error that will be encountered again after the Second Vatican Council:

To ensure more rapid progress day by day in the path of virtue, We will that the pious practice of frequent confession, which was introduced into the Church by the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, should be earnestly advocated. By it, genuine self-knowledge is increased, Christian humility grows, bad habits are corrected, spiritual neglect and tepidity are resisted, the conscience is purified, the will strengthened, a salutary self-control is attained, and grace is increased in virtue of the Sacrament itself. Let those, therefore, among the younger clergy who make light of or lessen esteem for frequent confession realize that what they are doing is alien to the Spirit of Christ and disastrous for the Mystical Body of our Savior.

Contempt for Personal Prayer

Some argue that only public liturgical prayer has any real value. This is how Pius XII describes this error:

“There are others who deny any impetratory power to our prayers, or who endeavor to insinuate into men’s minds the idea that prayers offered to God in private should be considered of little worth, whereas public prayers which are made in the Name of the Church are those which really matter, since they proceed from the Mystical Body of Christ.”

The error will be encountered again, in aggravated form, after Vatican II. It will go so far as to claim that the priest should not celebrate alone in the absence of the faithful. But Pope Pius XII has already answered this claim:

“This opinion is false; for the divine Redeemer is most closely united not only with His Church, which is His Beloved Spouse, but also with each and every one of the faithful, and He ardently desires to speak with them heart to heart, especially after Holy Communion. It is true that public prayer, inasmuch as it is offered by Mother Church, excels any other kind of prayer by reason of her dignity as Spouse of Christ; but no prayer, even the most private, is lacking in dignity or power, and all prayer is of the greatest help to the Mystical Body in which, through the Communion of Saints, no good can be done, no virtue practiced by the individual members, which does not redound also to the salvation of all.”

“Neither is a man forbidden to ask for himself particular favors even for this life merely because he is a member of this Body, provided he is always resigned to the divine will; for the members retain their own personality and remain subject to their own individual needs. [cf. St. Thos., II-II, q. 83, a. 5 et 6.] Moreover, how highly all should esteem mental prayer is proved not only by ecclesiastical documents, but also by the custom and practice of the saints.”

Rejection of Direct Prayer to Christ

A final error, which again comes within the competency of the liturgy, is the assertion “that our prayers should be directed not to the person of Jesus Christ, but rather to God, or to the Eternal Father through Christ, since our Savior as Head of His Mystical Body is the only ‘Mediator of God and men.’ (1 Tim.2:5).” Pope Pius XII responds: “But this certainly is opposed not only to the mind of the Church and to Christian usage, but to truth. For to speak exactly, Christ is Head of the universal Church as He exists at once in both of His natures, [cf. St. Thos., De Veritate, q. 29, a. 4, c.] moreover He Himself has solemnly declared: ‘If you shall ask me anything in my name, that I will do’” (Jn 14:14).

“For although prayers are very often directed to the Eternal Father through the only-begotten Son, especially in the Eucharistic Sacrifice—in which Christ, at once Priest and Victim, exercises in a special manner the office of Mediator—nevertheless not infrequently even in this Sacrifice, prayers are addressed to the Divine Redeemer also; for all Christians must clearly know and understand that the man Jesus Christ is also the Son of God and God Himself. And thus, when the Church Militant offers her adoration and prayers to the Immaculate Lamb, the Sacred Victim, her voice seems to re-echo the never-ending chorus of the Church Triumphant: ‘To him that sitteth on the throne, and to the Lamb, benediction, and honour, and glory, and power, for ever and ever’” (Apoc. 5:13).

The neo-liturgists sought to turn this condemnation to their advantage. They proclaimed, against the obvious, that the encyclical was “a great confirmation of the achievements of the Liturgical Movement” (Ferdinand Kolbe, The Liturgical Movement). Incidentally, they did the same with the encyclical Divino afflante.

They were deeply immersed in the mistake denounced by St. Pius X: they represented the future of the Church, and the hierarchy would approve them sooner or later. Which would unfortunately happen at the Second Vatican Council.

(Source - FSSPX - FSSPX.Actualités - 21/03/2020)