50 Years of the New Mass: Liturgical Revolution and Reaction of the Hierarchy (16)

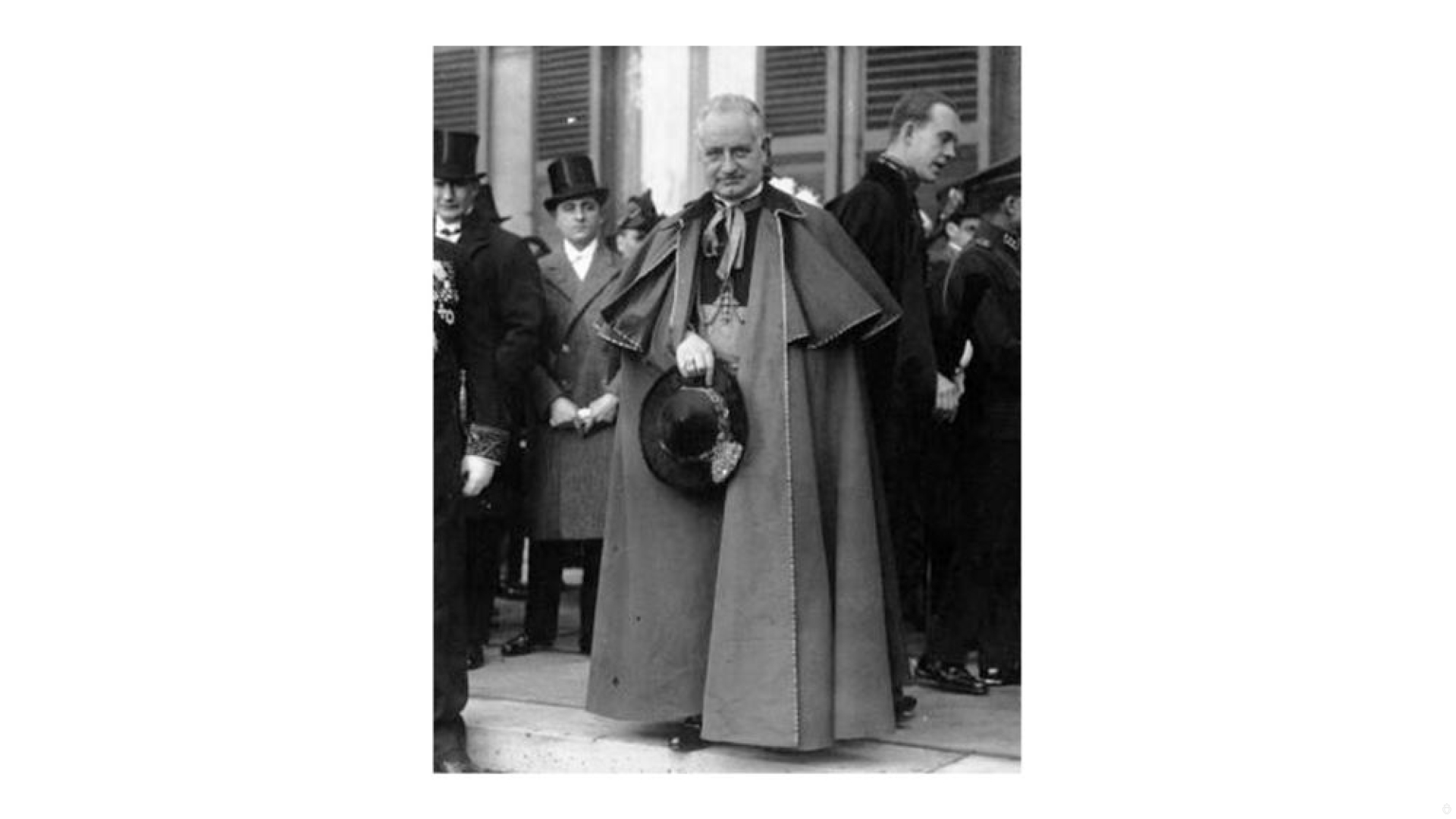

Cardinal Luigi Maglione

During the Second World War, the German clergy found themselves confined to churches and sacristies by the anti-Christian government. However, they did not remain inactive. Among the innovators, a veritable liturgical revolution was being prepared and developed. The ideas of Dom Odo Casel, Fr. Romano Guardini, Fr. Pius Parsch were thus gaining ground.

The forces then reacted: a wave of protest arose in all Catholic circles. The controversy, at first verbal, was repeated in two works: Irrwege und Umwege der Frommigkeit (errors and deviations of piety) by Max Kassipe, and Sentire cum Ecclesia (to feel with the Church) by Doerner. These books, which were openly hostile to the German Liturgical Movement, pushed the leaders of the movement to put their affairs in order. Rome would not tolerate disorder, sanctions were imminent.

The Maneuvers of the Innovators

To avoid condemnation from Rome, a private assembly, held at Fulda in August 1939, appointed as leader of the movement Bishop Landesdorfer, O.S.B., of Passau. His assistants were Fr. Jungmann and Romano Guardini.

The first necessity was to gain control of the German episcopate. Their moves were skillful: “The controversy was going from bad to worse. The German episcopate resolved at the Bishops’ Assembly at Fulda in August 1940 to take liturgical affairs in hand themselves. In charge of liturgical questions, the assembly appointed, at the instigation of Msgr. Landesdorfer, Msgr. Stohr from Mayence [the intimate friend of Guardini],…and Msgr. Landesdorfer of Passau himself.”

This “liturgical group” surrounded itself with “expert” specialists and “periti” who were none other than the leading lights of the German movement. Therefore, in one year, the trick had been

played, “the Trojan horse had entered the city”: the German Episcopal Assembly was in the hands of the “Renewal.”

A Clairvoyant and Courageous Reaction

The reaction was quick. In January 1943, Msgr. Conrad Gröber, Archbishop of Freiburg- Breisgau, addressed to his colleagues in Germany (in the “Greater Germany” that followed the Anschluss) a long letter written in a grave tone, that set out in seventeen points the principal causes of anxiety which he had about the youth movements. Here are the points related to the liturgy.

Point 1: The notorious spiritual schism among the clergy of Greater Germany, some being partisans of the movement and others being opposed to it.

Point 5: “What disturbs me is the radical and unjustified critique of all that has been accepted until now and all that has appeared in the course of history, and at the same time the practical, audacious, and brutal return to the practices and the norms of ancient periods of Church history, while openly declaring that in the meantime there has been an ‘evolution which is necessarily a deviation.’” Msgr. Gröber is here most certainly alluding to the archaeologism of Maria Laach.

Point 13: There is excessive emphasis on the common priesthood to the detriment of the ministerial priesthood.

Point 14: Particular insistence on the idea of “sacrifice-meal” and “meal-sacrifice.”

Point 15: The excessive insistence on the liturgy. It is claimed that only the liturgy can provide a true pastorate and earlier forms of apostolate are ridiculed. At the same time the rubrics are treated in a most cavalier fashion and all kinds of eccentricities are permitted.

Point 16: Efforts to make the dialogue Mass obligatory. This has been, from the start, one of the pet subjects of the Liturgical Movement. In 1922, Pope Pius XI gave his authorization for it, provided it had the permission of the local Ordinary. In 1923, Dom Gaspar Lefebvre published an apologia for the dialogue Mass in the learned review La vie spirituelle.

Archbishop Gröber wrote: “I have not the slightest objection to dialogue Masses as such, so long as their frequency is limited....They may be tried, but one must not hope for too much. Even so, I will always consider the dialogue Mass of marginal importance, and as something of momentary interest that soon the laws of change and of reaction will moderate and will cause to go out of fashion.”

This wise bishop was most worried by the discovery “that the neo-liturgists saw in the dialogue Mass the expression of their ideas about the common priesthood. They also saw a method for insisting on the rights of lay people to cooperate in the Sacrifice of the Mass.” This “activist” participation upheld by the idea of the general priesthood was what so worried the Archbishop of Freibourg. Here again Pius XII echoed this worry in Mediator Dei, condemning the new theology of the priesthood and imposing limits on the dialogue Mass.

Point 17: The strong tendency not only to translate into German more than one prayer during the administration of the sacraments, but also to anticipate the desires of the people by introducing the German language into the Mass itself despite the “non expedire” of the Council of Trent (Session XII, c.8, can.9).

The Archbishop of Freibourg concluded his letter in these moving terms: “I submit all these concerns to the Venerable Episcopate in order to acquit myself of my responsibility pro parte mea.... I could lengthen this list of things which worry me by adding more than one equally problematic point, points which seem to me contrary to Catholic doctrine. Can we remain silent, we bishops of greater Germany, and Rome?”

The Roman Reaction

Rome acted very quickly. By a letter from Cardinal Bertram, Archbishop of Breslau, to the members of the Episcopal Conference at Fulda, the Holy See made known its deep concern about the German Liturgical Movement, its desire to receive information on this subject, an appeal for vigilance by the Ordinaries, the forbidding of any discussion on the subject, and finally its readiness to examine with kindness certain privileges which might be helpful for the good of souls.

In the face of this danger to the movement, the German Episcopate energetically supported the neo-liturgists. On February 24, Cardinal Innitzer replied to Msgr. Gröber that the situation in Germany and Austria was not as worrisome as he implied… an intervention of the Magisterium would run the risk of discouraging the enthusiasm of the liturgists

However, this intervention which was so feared did take place. It was made on two separate occasions, by the encyclicals Mystici Corporis and Mediator Dei. Pius XII's vigorous “applying the brakes” would certainly have saved the situation, if at the same time the Secretariat of State had not encouraged the German movement by the concession of special privileges. Indeed, in April 1943, Cardinal Bertram sent a memorandum to the Holy Father in the name of all the other bishops. The memorandum was a universal and ardent defense of the Liturgical Movement. It judges that an entirely Latin liturgy is little fitted to encourage the participation of the faithful. It defends the “People’s Mass,” the “Sung People’s Mass,” and the High Mass in German. The Cardinal profits from the occasion to propose some reforms: prolonging beyond war time the mitigation of the Eucharistic fast, a new Latin translation of the Psalter,…the transferring of the Maundy Thursday and the Good Friday ceremonies to the evening.

Cardinal Maglione, Secretary of State, replied on December 24, 1943. In his reply, writes Ferdinand Kolbe, critical observations are not lacking, it is true, but the decision on the manner of celebrating the People’s Mass and the Sung People’s Mass is left to the discretion of the bishops, and the High Mass in German is expressly permitted. The letter ensured the later development of the celebration of the Mass in line with the Liturgical Movement under the bishops’ protection.

Did the Secretariat of State know that the bishops of the German Liturgical Commission, to whom it gave the responsibility for the form of the celebration of Mass, were amongst the most advanced members of the movement?… There are so many questions which are unanswerable. But what is certain is that here we see the first victories of the deviated Liturgical Movement over the Roman authorities.

Thus, at the end of World War II, the Liturgical Movement had considerably strengthened its position. It had brought about a powerful vehicle of liturgical subversion: the Center of Liturgical Pastorate. And above all, it had perfected its tactics for war: win over the bishops to its cause and thus to act legally, and have its requests presented to the Holy See by the bishops, on the pretext of pastoral advantages.

Related links

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Pius Parsch (15)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Maria Laach Abbey (13)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Romano Guardini (14)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: St. Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (9)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Gaspar Lefebvre and His Missal (10)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The National Center for Pastoral Liturgy (12)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Saint Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (7)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: St. Pius X and the Liturgical Movement (8)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Lambert Beauduin and the Liturgical Movement (11)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Guéranger and the Liturgical Movement (5)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Fr. Emmanuel, Parish Priest of Mesnil-Saint-Loup (6)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Making of the Roman Missal (1)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Development of the Roman Missal (2)

- 50 Years of the New Mass: The Tridentine Missal Put to the Test by Gallicanism …

- 50 Years of the New Mass: Dom Guéranger and the Liturgical Movement (4)

(Sources : Le Mouvement liturgique (Abbé Bonneterre) – FSSPX.Actualités - 14/03/2020)